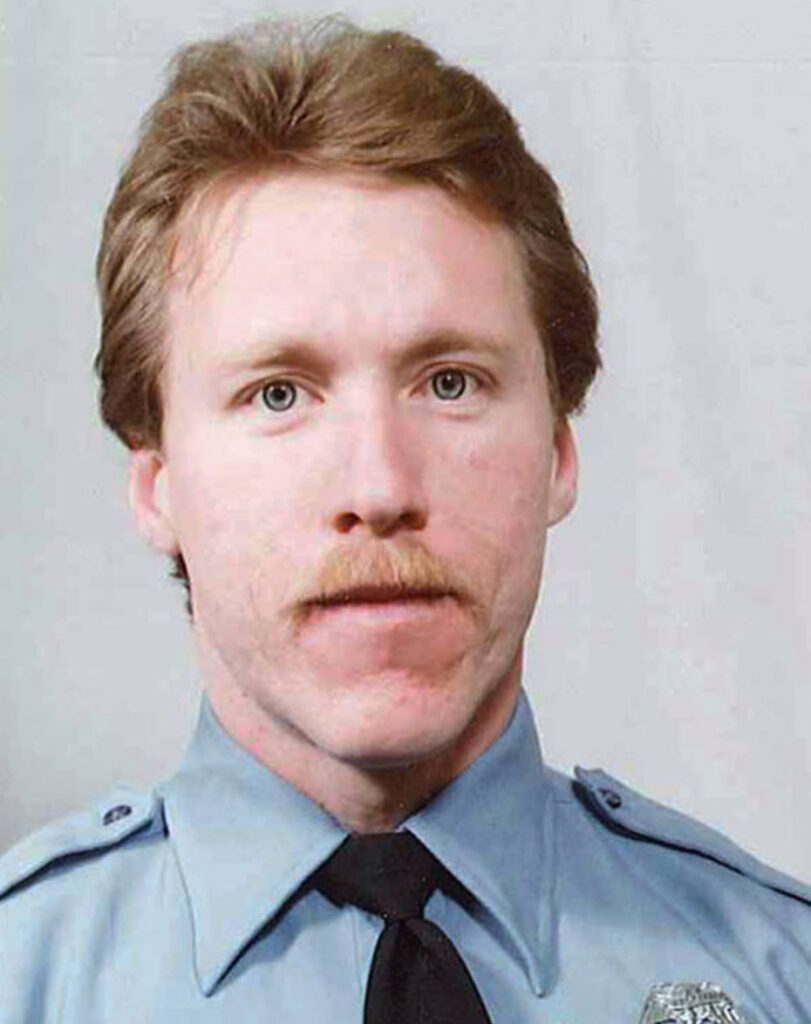

Bruce Helppie is retired police officer for the City of Toledo. He received the The Blue Star after being wounded in action in 1984. He is a graduate of Eastern Michigan University and specializes in martial arts and body building.

Bruce Helppie

Transcript of Episode 60 with Bruce Helppie

Episode 60- With Rich and Bruce Helppie

Brian Kruger:

Welcome to the podcast the Common Bridge with Richard Helppie. Rich is a successful entrepreneur in the technology health and finance space. He and his wife, Leslie, are also philanthropists with interest in civic and artistic endeavors, but with a primary focus on medically and educationally under-served children. My name is Brian Kruger and from time to time, I’ll be the moderator and host of this podcast.

And welcome to the Common Bridge. This is our 60th episode, and Rich is proud to have a retired police officer as his guest today. And I’ll have him introduce that guest. This is going to be a two part podcast, so it’ll run today and next week as well. So let’s join the Common Bridge in progress.

Rich Helppie:

Welcome to the Common Bridge. I’ve got a really special episode today that has to do with policing in America. And as my listeners know, I will go find experts and do some research. And sometimes you don’t have to go far to find an expert to give you real world experience. And so my cousin, Bruce Helppie, is our guest today. Now, Bruce, I will tell you this, is one of the most fair human beings that I know. He is the most stand-up guy. He graduated from college with a degree in history and he joined the police force in an urban setting. He’s a very focused guy, he’s a power lifter, a martial artist. He earned the Blue Star for an incident where he was, again, very heroic and defending his partner and resulting in taking gunshot wounds himself-was very seriously injured and thankfully survived that. He’s earned service award recognition and he’s got a great perspective that I think our listeners are really going to enjoy. Bruce, so glad you’re on the Common Bridge.

Bruce Helppie:

Well thank you for that nice introduction and the only correction I’d make was I was a police officer for almost 31 years.

Rich Helppie:

Right. It’s been 31 years, part of that’s because you look so young. Bruce, talk to our listeners just a little bit about your experience when you were with the police force, what kind of patrol duties did you have? Who are some of the partners that you rode with, and maybe what are some of the key things that stood out in your mind from that 31 years of experience?

Bruce Helppie:

Well, like most policemen, or almost everybody, went through an academy that was sponsored by the Toledo police. I went through their in-house academy. It started in September and it ended in January, however many months that is, four or five months. They send you out on FTO kind of, what they called it at the time wasn’t really FTO training. You did kind of ride along, so even before we got out of the academy, they sent us out with officers. When you graduated, you went to street duty, which I believe everybody in my class did. We were the largest class in the city of Toledo at the time. We had 130 recruits, about 120 of us graduated.

I had partners, we were assigned to partners and field operations. For the first couple years we rotated through the shifts. So they had, at that time, I don’t know what they’re doing now, I’ve been retired for six years, but we had typical days, afternoon, midnight shifts. And there was an eight at night morning, an overlap shift that I never worked till the end of my career. So you’d typically be on one of those shifts for four months at the time I went on.

And you were assigned a veteran partner, assigned in the inner city, I worked with Keith Miller and we’d been working all of a week when we were sent to a domestic violence that turned bad. We were kind of blocked on the stairway. We were admitted into the house by a young girl. The police had been called, we were dispatched to the call. We were blocked by about a 285 pound man, didn’t want to let us upstairs. The call was that he was beating his wife with a two by four. He blocked the stairs, he’s screaming and yelling at us. As we came up the stairs, my partner, Keith, we kind of basically said, well, you’re under arrest. And we got in a struggle on a stairwell-I’m not going to go into the whole play by play of what happened-but during the process of coming down the stairs, somehow he was able to pluck my partner’s gun out of his holster. And he shot both of us. I was shot several more times in the close quarters that the shooting occurred. I was able to grab the gun twist it back and in the guy’s direction, he shot himself and he bled out. My partner and I both had multiple gunshot wounds. My partner was shot four times-two in the face. I was hit three times. I also got disarmed during that encounter and was shot with my own gun. So I was shot with my partner’s gun and we were both shot with our own guns, and with the partners gun. That was the first kind of real domestic I’d even been to. They told us in the academy how those things can go bad, really, in a heartbeat. And I found out the hard way they do or can.

Rich Helppie:

I remember that distinctly, was probably one of the worst calls I’ve ever gotten and being down there to see you. You probably don’t remember that I was there.

Bruce Helppie:

Well, actually I do. I remember a lot of people who came, I got a lot of support. It was overwhelming, really. I even got cards from people I didn’t know. I don’t know if anything was screened, remarkably I didn’t get death threats or hate mail.

Rich Helppie:

We’re going to lead into this in these times, but you and Keith Miller, white officer and a black officer, became very good friends.

Bruce Helppie:

Keith and I were only partners for that one week. We never worked together again. I was off work for several months. Keith was off, I think from March until about December. We never worked together again. We-just coincidence, put us at another call like 25 years after this one, where we were in a second shooting together, but we weren’t partners at the time. He was a sergeant, I was a patrolman and we just happened to both wind up at the same call.

Rich Helppie:

Well, I know that during that incident, and I know you’re being modest, that when the perpetrator got a hold of Keith’s weapon and discharged it, hit both of you, that you rustled him with one hand and got the gun pointed down. And what I want our listeners to understand is that we’ve talked on this program before about the very difficult job of a police officer. That in the course of a shift, or in fact, in the course of a few minutes, you don’t know if you’re going to a domestic dispute, a neighborhood argument, a lost pet, a wellness check, an alarm’s gone off, a clearly mental health issue-because it’s never evident immediately or not often evident immediately that it’s mental health, and at any time, perhaps things explode into a violent confrontation. So Bruce, you handled all those calls, I’m sure.

Bruce Helppie:

Pretty much I’d say quite a few of them.

Rich Helppie:

So there’s this portrait we’re getting painted in certain places of the media that angry, blood thirsty police officers are trying to hunt down members of the community. Is that what your experience was? Or how would it differ?

Bruce Helppie:

Here’s what officers are doing. They’re reacting how they were trained. What the public doesn’t quite understand is that, at least the way I was trained and it’s sanctioned by the state of Ohio and it’s probably pretty much the standard around the country, officers are allowed to use a higher level of force than that being used against them. So if somebody comes at you with a knife, you’re allowed to shoot them. If they come at you with any kind of deadly weapon-a tire iron, a knife, try to run you over with their car, those are clearly situations where officers are allowed to use deadly force. Now there’s still judgment that has to be considered there. If somebody is a hundred yards away from me with a knife, are they going to be able to stab you? Probably not. There’s distance and size of an assailant. The common thing is fearing for your life, which gets criticized but that’s part of the equation too, I would say. But every department’s going to have a use of force policy. It’s written down, it’s usually worded in a fairly nebulous manner, they can’t spell out every situation that can possibly happen, so it revolves around generalities. And then I guess it’s going to be judged later by the events that happen.

Rich Helppie:

We had Sheriff Jerry Clayton on the Common Bridge earlier, and he talked about the officers arriving on the scene, and in his case, sheriff deputy, is arriving on the scene and their first responsibilities, to see if they can de-escalate, create space, set up a perimeter, try to avoid an escalation. Has that been your experience or do you see the police officers being more aggressive, trying to get in, take care of something as quickly and as aggressively?

Bruce Helppie:

Sometimes there’s direct action that needs to be taken and other times there isn’t. I’ve been in standoffs. I mentioned a second shooting I was in with Keith Miller. In that situation, the man’s wife called. They were riding in a car together. She said he was talking crazy and he had a gun. He got out of the car, he was walking. So they sent me, Keith Miller. We came from different directions. I came around a corner and I saw Keith out in the middle of the street. Well, this guy had a gun in a holster on his side, and Keith’s pointing his gun at him, telling him to get his hand off the gun. We ended up in a debate with the guy, tried to talk with the guy. And he ended up pulling out a second gun. Well first, he pulled a gun and pointed it at his own chest. So there was negotiation while he was a suicidal man. Well, then he came out with his left hand, with a second gun, pointing in the direction of Keith and other officers. Three officers shot, three didn’t. I did not shoot that time. That guy was shot and killed right on the street. We’ve had other incidents like where we had Joseph Chapel, who went on a shooting spree. He shot an ex-girlfriend, he car-jacked a car, he shot a fireman, he attacked a fire truck that was going to help victims, shot some girls, stole another girl’s car-a pizza delivery driver-shot and killed her. And the police chased him down and shot and killed him in a Kroger parking lot. He careened in there and he’d obviously been on a murderous rampage. So there wasn’t really any negotiating. He got out with, I think, a shotgun and he was blasted by three officers and killed on the spot. I don’t know if there’s really a single answer to that. Sometimes there’s negotiation, if you can negotiate. And other times, negotiations aren’t in the picture.

Rich Helppie:

Well, let’s turn to some of the specific things that have been in the news. In particular, I’m looking for both your viewpoint and then maybe we try to talk a little bit about policy answers. So the bank robber-come back to him-pointing his gun at his head. You have armed officers, armed person that’s obviously disturbed and has just engaged in criminality and led officers on a chase. Is there any window there for intervention by mental health worker, social worker, or anything of that?

Bruce Helppie:

I would say not in that case. Obviously you’ve got a bank robbery, you’ve got a federal crime combined with a high speed chase through Toledo, that lasted 45 minutes. The guy was taken into custody. He was not injured. That one we were able to, there was like a perimeter, he was kind of boxed in and he decided not to shoot it out or do something that was going to create his own demise. So he was taken in, he wasn’t injured at all. I believe, I don’t think, he had anything other than handcuffs on his wrist. That’s really the goal with officers, I think, pretty much around the country. I remember Keith Miller, one of the things-I had been in other calls with him later on in both of our careers-I remember him talking to people and said we could do things the hard way or the easy way. And he goes, I’d rather do things the easy way. And that’s the mentality I have. I’d rather not get in trouble, not get hurt, not hurt anybody. I think that’s the goal of most policemen.

Rich Helppie:

I agree with that, that’s what we’re all after is good policing, the appropriate amount of service. So Bruce, some cases, and I know we probably can’t dissect them in great detail, but Michael Brown. And you and I may have a little different view on that, but as a very seasoned police officer, a lot of street experience, your view on Michael Brown if you care to share it? If you want to pass, we’ll go to the next one.

Bruce Helppie:

I thought the false narratives kind of started. That happened right after I retired. I retired in June of 2014. I believe that happened in maybe August of the same year. From the accounts that I saw, Mike Brown went into a carry out. Mike Brown was about six foot five, 300 pounds, from what I read. He went in the carry-out, decided to steal cigars from the carry out. There was a little Asian man that was the owner-or the manager, a clerk, whatever he was-at the time. He came in front of Mike Brown, basically saying-it looked to me like he was saying-it was a video that didn’t have any audio to it-and wanted payment for the cigars. Mike Brown drew his fist back as if he was going to hit him. I think Mike Brown-like I said 6’-5”, 300-this (worker) guy looked to be five foot six, 130 pounds. In police parlance that would be a strong arm robbery. He was threatening force-a theft offense combined with force equals robbery. In Ohio it’s a second degree felony. So he walks away from the carry out. He’s walking down the street, in the middle of the street, him and a friend, I think there was two of them for what I remember. The officer, I believe his name was Darren Wilson, drives up, tells him to get out of the street. But I don’t know at what point, if during that call or as he stopped to tell him to get out of the street, he got word of a robbery or potential theft, whatever, from this carry-out. So he stopped to question them about that. Well, Brown came up to the car, punches through the open window, punches Wilson in the face several times. Wilson’s gun goes off in the car, whether Brown was grabbing it, or Darren Wilson was trying to get the gun. I don’t know what happened there, but a shot went off. So Brown leaves, Wilson gets out of the car and Brown decides to start walking back to the scene. I don’t know everything that happened there, but Wilson opens fire on him. Then there’s the question of how far away was he? So you have a couple different crimes here. He was unarmed. Should he have been shot? Was he a threat to Wilson? He could have charged up the hill at him or ran at him. There’s probably a likelihood he’d probably try to disarm him if he was trying to disarm him in the car. That’s basically my take on it.

Rich Helppie:

I know that the Obama justice department, through Eric Holder, did investigate the shooting and said there was no violation of civil rights at all. What I’m puzzled by is this, one of the allegations was that Michael Brown had reached through the car window and got the gun of the officer. And I’m thinking, I don’t know how a guy that big can fit through a window and reach across an officer, all that big and get to the gun. It just didn’t seem to make any sense to me. And that if Michael Brown was shot that at that point, now you have someone that’s wounded, they’re traumatized, the officer’s in fear, they’re yelling at each other. We know that Michael Brown was returning toward the officer. Now, whether he was aggressive or whether he was following a command, we don’t know. But at that point, the officer fired and again, the officer was ultimately exonerated.

Let’s move to George Floyd. I know, Bruce, that you watched some of the video with George Floyd. And you said you had been in similar situations. And I think when we were chatting about this weeks ago, you said you probably would have had him sit up, given him some water, and asked him if he was done with the struggle and maybe take him to the appropriate place, medical or jail. From the officer’s point of view, what did you see as you watched the films about George Floyd?

Bruce Helppie:

If you just see the one that they showed on the news, initially, it looked pretty bad, looked pretty bad for Derek Chavin. Looks like he’s just kind of torturing this guy, holding him down with his knee on his neck. I’m going, that doesn’t look like anything that looks like standard police practice to me. But I also did reserve judgment on that because you’re allowed to do what your department trains you to do. And I haven’t really heard where his department said that he could or couldn’t do that. Nobody had come forward and denounced that tactic saying, well, he’s never allowed to put a knee on somebody’s neck. Some departments outright ban choke holds-now a lot of them probably are in the wake of all this, they seem to be. But recently I’ve read where his department will even allow the knee on the neck. And I saw a subsequent video that, I think it was from one of the other officer’s cars, it showed the initial stop with them getting Floyd out of the car. And he wasn’t really all that cooperative. They got them out. And once they handcuffed him, he started kind of freaking out. A large person like George Floyd, a lot of times, they’re not going to fit real well in the back of a police car. I think he was six foot eight. George Floyd decided to fling himself to the ground. Chavin appeared to, it seemed to me that he felt like he was doing something that he was allowed to do. I’m watching that and going well, is he allowed to do this? I was never trained to do that, to put a knee on somebody’s neck. And we were also trained, with somebody that’s handcuffed with their hands behind their back, which is standard-they didn’t want us ever handcuffing anybody in front-that we were allowed some exceptions if somebody had physical deformities or obvious injuries where you would have to handcuff them in the front, then you’re supposed to use a belt to help hold their hands down so they couldn’t use them against you. Anyway, there’s a thing called positional asphyxiation from being on your stomach-sort of a hog tie position. So I’m watching the initial video thinking, well, why aren’t they kind of sitting him up? He’s saying he was giving up. So I think that part’s kind of problematic for Officer Chavin. But then he’s mitigated quite a bit by the idea that his department allows him to do that, even the knee on the neck, from what I understand.

Rich Helppie:

And I think that some of the public outrage is that the knee on the neck shouldn’t be something allowed by the officers representing us.

Bruce Helppie:

I was shown some restraining techniques where you would use your knee against the side of somebody’s head to keep them pressed down on the pavement. If your head’s pinned to the ground, it’s hard to move. I don’t think much risk of death with that. That’s what I kind of question-you pin the head, but then you do it for the length of time-you get somebody handcuffed and if they’ve calmed down, take it off. If they’re screaming, kicking, and trying to bite you, maybe you keep them down longer. But Floyd was signaling he was giving up. I think they probably could have sat him up. And like I said, I kind of go by whatever his department, whatever their training section tells them they can or can’t do. If he was trained to do that and that’s what he did-like I said, I haven’t heard any disavowals from the upper command of the Minneapolis police department. I haven’t heard a training officer or even the chief come out and say, well, this is strictly prohibited what he did, he went outside his training. I haven’t heard anybody say that.

Rich Helppie:

And I think that’s the root of it. So just a couple of observations I’ve made as a civilian in this. First of all, that the officer was-when he’s kneeling out his neck, got his hands in his pockets-he’s just like casually sitting there.

Bruce Helppie:

That’s what I thought I saw. I’m not sure, somebody said he had a glove on, but I thought he had his hand in his pocket. And I don’t know if you take that as he was torturing the guy or if he’s not applying that much pressure, he’s just thinking he’s holding them down. So that’s why I said, I’d kind like to hear Chavin, what his explanation for what he was doing.

Rich Helppie:

And then I think it begs the other question, when I saw this, the initial encounter with George Floyd, when another passenger in the car, a woman said, George kind of isn’t right in the head. And it was obvious to me watching it, that he was in distress from the moment-and whether it was emotional or psychological or he had a lot of drugs on board at that time-he really wasn’t right. And I don’t know that he could have responded to commands. And so I’m just saying from a policy perspective, is there another way, could a perimeter be established and a different kind of…

Bruce Helppie:

Here are some other issues you have with George Floyd, because I’ll hear, he wasn’t doing anything, he was giving up. Well, first of all, he went into a store, I think it was that he was trying to pass a counterfeit bill. I believe it was either a counterfeit bill or a bad check-but I think it was a counterfeit bill. That’s a crime that merits investigation. And then he goes back to the car and he’s sitting in the driver’s seat. So if he’s intoxicated on drugs, should he be sitting in the driver’s seat? I don’t know if the keys were in the ignition or not, but that’s essentially a DUI. Coroner reports have said he had fentanyl and various other drugs in his system, I think methamphetamine was another one.

Rich Helppie:

I think we can all agree, nothing he was doing warranted a death sentence, no matter what.

Bruce Helppie:

Exactly. He shouldn’t have died, but then I think the question still becomes, okay, did he die because of a knee on the neck? Or did he die because he was so geeked up on illegal drugs that just the added stress of resisting arrest and his own emotional state created-I don’t know if he had a cardiac arrest, I’m not sure what they are saying the cause of death was.

Rich Helppie:

The city was burned down. If you were the mayor of Minneapolis and you said, I don’t want to get the city burned down again. Would there be any policy changes or would it be something more about how to guide people when they interact with the police force?

Bruce Helppie:

Well, it’s unpopular to say this, there’s false narratives around pretty much all of these police killings or police deaths, deaths at the hands of police. If you watch the news, they portray all these incidents as if the person that ultimately died was a completely innocent person, who hadn’t done anything, that the police showed up and killed them. And it’s counterproductive because, a couple of things, one, it encourages people to resist arrest. And when people resist arrest, the police are going to escalate force. That’s just how they’re trained everywhere in the country. Every police department in the country is going to basically give the police a green light when people start fighting with them or resisting arrest, to up the ante. So tasers come out or nightsticks or guns if it reaches that level. So it’s going to get more people hurt. It’s also going to get more police hurt because people are going to be violently resisting, because they think they don’t have to follow the law. I’ve said that much more good could be accomplished if public service messages were put out that when you’re driving a car, it’s required by law to have your license on you, you sign off on that when you get your driver’s license in any state. That you’ll produce your license on demand of police and that resisting arrest, there’s a good possibility you’ll get injured. If that was the message that was sent out, instead of, resist the police, they can’t stop you, you’re not doing anything wrong-whether you strong arm rob the store, you passed out drunk in the drive through at Wendy’s, were politely walked through your DUI field sobriety tests then decided to fight with the police when they arrested you, disarm one of his taser, these things wouldn’t happen. It’s not up to you to be the judge or jury too, of encounters with the police, that’s up to the courts.

Rich Helppie:

I think that the chief of police in Detroit would agree with what you said. There was an incident that we talked about not far from the place that you and I spent a lot of our childhood, but a young man pulled a firearm on police officers, they shot him.

Bruce Helppie:

He just missed one, I think it went right past his head and the other, one of the officers shot and killed the kid. And until I saw where chief Craig had put out the video, because they were already rioting and making a big stink. And the police aren’t out there to be cannon fodder. The job’s dangerous enough. They’re not obligated to be killed because somebody wants to act up. They don’t have to wait to be shot to return fire.

Rich Helppie:

Well, I think that’s what James Craig said recently, when protesters assaulted police with rocks and railroad spikes and fireworks, there was no call to investigate them, but there were some congressional reps and others grandstanding about wanting to investigate the Detroit police department and including trying to get courts to order that the Detroit police cannot use batons, shields, gas, rubber bullets, choke-holds, or sound cannons against peaceful protesters. And I don’t think, a peaceful protest, you wouldn’t need to do anything like that. But the definition, I think, a peaceful protest is morphed now to include arson, quite frankly. And we’ve all seen the videos of reporters saying the protest is mostly peaceful. And I know, Bruce, you and I as a couple of ballplayers, you probably saw the film from Portland where the guy with the weakest arm in the crowd, threw the Molotov cocktail and lit other people that were out there protesting or doing civil unrest.

Bruce Helppie:

I saw a partial interview with a Portland officer, I don’t know who the interviewer was, it was on YouTube. There was, I believe he was a patrol sergeant, and he had been at ground zero of these riots or protests, whatever you want to call them, I’ll call them riots because that’s basically what they turned into. And there was a Nazi riot in Toledo, before I retired, it was probably about 14, 15 years ago, that turned into a pretty big deal. It was on CNN. I was at ground zero of that on the street, in the front lines of that. You don’t know who the peaceful protesters are because everything’s chaotic. And there’s people that probably wouldn’t hurt harm a fly, holding the signs and walking and they might be yelling things at the police, but they’re not really going to hurt anybody. But then there’s, I guess, infiltrators or people that are taking advantage of the situation to be violent, as you said, arson, commit arson and assault the police. They were shooting firecrackers and I forget what they’re called, class B or C fireworks or projectiles, they’re firing them at the officers, throwing bags of urine. He said the guy with the Molotov cocktail that was intended for the police, it hit his own people in his crowd. I think you’re right. I think it morphed into something that isn’t a peaceful protest anymore. And I think it’s really becoming counterproductive.

Brian Kruger:

That’s going to be a good breaking point for this episode and we’ll pick this conversation that Rich has having with his cousin, retired police officer Bruce Helppie, next week on the Common Bridge.

You have been listening to Richard Helppie’s Common Bridge podcast. Recording and post-production provided by Stunt Three Multimedia. All rights are reserved by Richard Helppie. For more information, visit RichardHelppie.com.

Search

About This Site

The Common Bridge was set up to provide a space for discussing policy issues without the noise of political polar extremism enflamed by broadcast and print media.